Technocratic and managerial reforms spreading around the world are built on the assumption that if teaching is executed with technical precision that constitutes “high quality teaching,” then equity and justice will emerge as a byproduct of these efforts. But equity and justice require moral and ethical commitments that go beyond technical skills. It is about choices of building relationships with, giving voice to, and recognizing the inherent value of students and communities that might have been historically ignored or actively excluded. Drawing from the work of decolonial scholars Achille Mbembe and Francoise Verges – in a world where some individuals and communities are seen as disposable, teachers have to actively fight those perceptions. Systems of injustice are like a moving walkway – just standing and doing nothing won’t reverse hundreds of years of damage done to racial, ethnic, linguistic, and social groups that have been historically excluded from access to education. Creating more equitable institutions requires intentional efforts to examine and disrupt inequities in schools and in educational policies.

Examples of centering equity and justice in teacher education policy are unfortunately less frequent that we might like to think. Teacher and teacher education policies in the US and around the world have turned towards more technocratic control that approaches equity in technical terms – recognition of diversity along various markers without accompanying representation, redistribution, or commitment to reparations to undo the historical harms. Equity and justice end up serving a performative role of signaling concerns without fully attending to the root causes that created inequities in the first place. In the United States, for instance, entities that have the power to set the standards for teachers and teachers education take up what Marylin Cochran-Smith calls “thin equity” – the focus on test scores of different groups rather than attending to deeper issues entangled in systems of oppression.

When I work with preservice teachers, I share a photo from an elementary school where children walking to the cafeteria are told to form a single file and place their hands behind their backs. When I ask my students what this reminds them of, they immediately recognize that this is how inmates walk in prison. This practice is normalized in US schools serving minoritized and historically underserved communities. It is part of what has been described as school-prison nexus that places minoritized students on a path to prison. What do teachers need to disrupt this systemic injustice?

One of the approaches that has been gaining ground over the past decade has been the focus on educators’ equity literacy that helps teachers recognize inequities, respond to them, redress them, as well as create and sustain equitable learning environments. Equity Literacy Institute founded by Paul Gorski has been emphasizing the importance of approaching equity by attending to student experiences in the context of overall school cultures, not just outcome measures on standardized assessments.

But to disrupt systemic injustices, teachers also need to engage with policies at various levels. Some scholars argue that raising one’s professional voice through policy advocacy is central in pursuit of equity and justice.

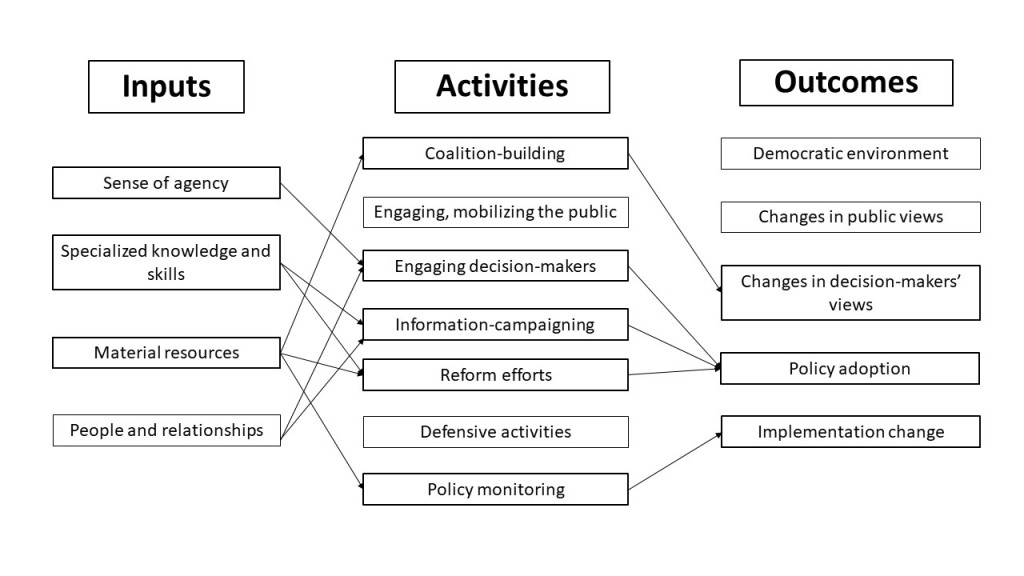

What is policy advocacy? Sheldon Gen & Amy Conley Wright define advocacy broadly as a set of “intentional activities initiated by the public to affect the policy making process” (p. 165). May Hara and Annalee Good define policy advocacy as “efforts taken by teachers to influence education policy toward equitable systems change” (p. 6). Teachers policy advocacy can include efforts to influence public opinion, agenda setting and policy design, as well as policy implementation, monitoring, and feedback. Among the benefits of educators’ advocacy are their proximity to classroom realities and direct engagement with diversity and equity issues. Participating in policy advocacy also strengthens teaching as a profession and keeps educators in the job.

Empirical research on advocacy has shown that it depends on a set of inputs that comprise advocates’ competencies and resources. Advocacy manifests itself through a variety of activities – from coalition-building to engaging with decision-makers. Its outcomes can include changed perspectives on policy, pilots, reforms, or evaluations of policy. When can educators influence policy? Educators have most impact on policy when they have support and resources for engaging in advocacy and have opportunities to participate in a variety of different advocacy activities.

What are the barriers to educator policy advocacy? Based on research, we know that there are at least three major barriers: limited knowledge of policy contexts, a lack of support structures, and a lack of inclusion of teacher voices in policy dialogues.

Let’s dive deeper. It is true that even educators who underwent professional preparation for teaching tend to feel underprepared for policy conversations. Most educators tend to focus on their classrooms and on their students’ immediate needs. As one teacher explained to us, it is “class home class home class home” cycle that keeps teachers away from considering policy issues.

“As teachers, there is so much that teachers don’t know and not because we don’t want to know. I just think that it just happens that way. We get stuck in our mundane day-to-day class, home, class, home, class, home, and we don’t really know what’s going on and how policy is created and all the things that we could do to actually make a difference for future teachers and students.” [Teacher, Policy Fellow, Interview 2023]

How the educational system works or where policies come from can sometimes seem like a daunting question to ask. To address this question, however, a growing number of preservice teacher education programs in the US have begun to integrate courses on educational policy. Those courses take up different ways of getting preservice teachers familiar with policy – from reading and analyzing policy texts, to preparing responses to policies and policy proposals. But preparation for policy advocacy is not a part of teacher standards. Teachers are often expected to implement policies designed by others. As a result, efforts to prepare teachers for policy contexts have been sporadic and not coordinated. Furthermore, the courses end up being reactionary: the emphasis remains on responding to what decisionmakers produce rather than designing or creating texts that could inform policy.

To engage in policy advocacy, educators have to develop a set of competencies. Those include the ability to communicate with diverse audiences (e. g., policymakers, media), ability to identify and define problems, ability to conduct research to address problems, ability to propose policy solutions, and skills of working with and alongside minoritized and historically underserved communities. Finally, articulating a vision of what equitable and just education should look like tops the list of competencies that teachers need for engaging with policies but rarely develop in education policy courses.

There is a growing number of efforts to prepare educators for policy advocacy at the in-service level. Professional organizations offer leadership institutes for teachers that give them basic competencies for engaging with legislators and policymakers. Hara and Good describe professional development opportunities like “unconferences” or collaborative mentoring that allow teachers to engage in collaborative problem-solving around the policies that concern them. Workshops focused on coalition building help teachers identify groups that are pursuing similar policy priorities in order to partner with them.

The problem that professional development initiatives run into is that even when teachers gain the knowledge and the skills necessary for navigating policy contexts, they remain uncertain about who they should turn to with proposals for policy changes. In that regard, policy fellowship programs have given teachers an opportunity to not only learn how policymaking works but also develop and maintain relationships with key decisionmakers over lunch, dinner, or scheduled informal conversations.

“A goal [is] to familiarize us with the people with some power and how to get in touch with them, because they usually end with, ‘Here’s my email and phone number. Feel free to reach out to me.’” [Teacher, Policy Fellow, Interview 2023]

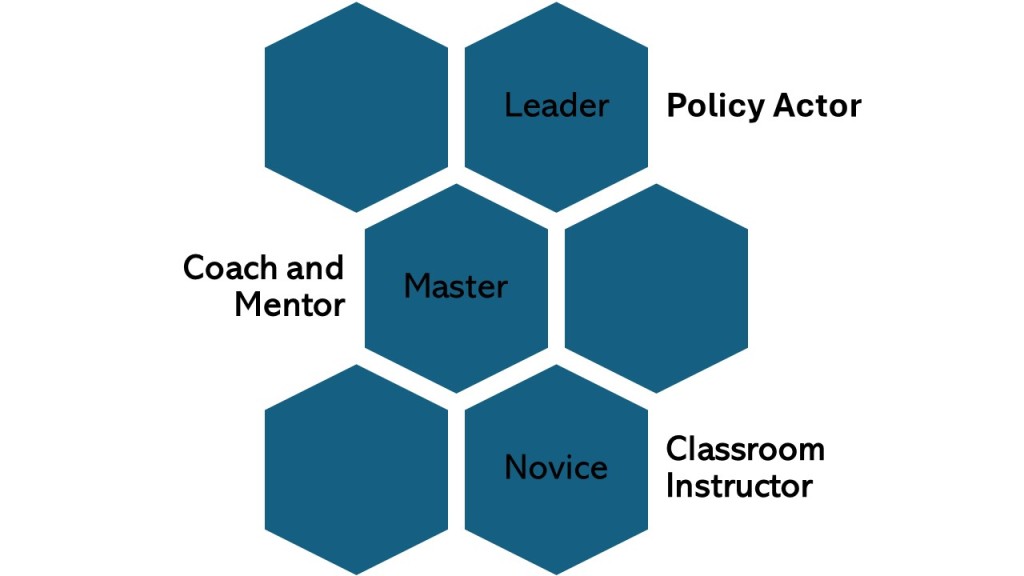

Another barrier to advocacy concerns resources. Having the resources to participate in policymaking is important and many educators note that they need support structures to ensure that they could have time off to travel to the meetings with decisionmakers or to attend professional development related to policy advocacy. What could potentially help is reenvisioning teacher career ladder. We know novice teachers need time to develop adaptive expertise to navigate classroom realities effectively. Once they do, in some countries, they become master teachers able to coach and mentor junior colleagues. But then what? Greater engagement in policy as a teacher leader could reenergize teachers who have passed the mastery stage. But those structures don’t have to be linear – some studies suggest that early engagement with policy helps novice teachers remain in the profession.

A much greater barrier to teacher advocacy across studies and across contexts, however, is the fact that teacher voices are simply not heard. In a survey of 20,000 American teachers only 2% of teachers noted that they felt that teachers voices were heard in national policymaking. 25% stated that teachers voices were not heard at any of the levels of policymaking. This exclusion of teacher voices is also visible in global conversations. For example, during one of the International Summits on the Teaching Profession, decisionmakers talked to each other while teachers were relegated to the role of observers. Those teachers were in the room but not at the table.

There are structures that would allow policymakers to hear from teachers – working groups, advisory boards, advisory councils, teacher leadership networks. There are now even systems where comments on proposed policies can be submitted via portals. In the United States, a model of negotiated rulemaking that includes the perspectives of stakeholders who are going to be affected by new regulations or laws exists as an option for including educators’ perspectives in policymaking. This model requires that representatives of the profession are involved in the deliberative process of regular meetings and discussions that are moderated by an external facilitator (not decisionmakers themselves). The issue is that this model is utilized in increasingly rare number of cases and is considered important only for the federal department of education, which has limited powers in the U.S. When in one of our studies teacher educators tried to introduce a bill that would require negotiated rulemaking for teacher educational policies in their state where most decisions that affect teacher education are made, they could not even find a sponsor for the bill among legislators. The proposal to include teacher educators in discussions of policies related to teacher education never saw the light of day.

Educators do not feel heard not because there are no structures for them to share their perspectives, or they don’t have anything valuable to say, or they are not trying, but because they are not trusted. Opinions of consultants, advisors, nonprofits, NGOs, philanthropists, and lobbyists are perceived as more credible than teachers’ perspectives. Decisionmakers simply don’t trust educators. What feeds this lack of trust is the constant talk of crisis and failure. However, this lack of trust and exclusion of teacher voice is also what contributes to this crisis and failure. Well-educated professionals do not want to stay in teaching jobs engrossed in constant crisis talk where someone else dictates what they have to teach, what they have to wear, and what they can and cannot say. When educators feel that their voices are heard and valued, they are more satisfied with their jobs and more likely to stay in them. Developing trusting relationships with educators is an important first step to addressing the challenges educational systems are facing.

The recommendations outlined above echo the recommendations provided in the report that was put out by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards authored by teachers. In that report, teachers ask that policymakers seek out and listen to teachers at scale – not just a few isolated individuals. They ask that policymakers trust, support, and encourage teacher leaders’ ambitions. And finally, teachers are asking that decisionmakers invest in teachers, particularly in solutions that strengthen practice and build leadership capacity.

To conclude, educators need opportunities to learn about advocacy and actually engage in it. But policymakers also have to make the choice to incorporate teacher voice in policy conversations and include teachers in policy deliberations. Investing in relationships of trust and respect might be a good place to start this process. When teachers provide feedback and input into policy proposals, those should not be dismissed as irrelevant or self-serving. With all the talk of accountability, we hardly ever hear of policymakers’ accountability to the teaching profession and to the students. Promises are made that reforms would improve teachers’ working conditions or help them stay in the profession, but they end up driving out more teachers than actually retaining. When that happens, there should be accountability for policymakers. There are groups in the US that rate policymakers on whether they kept election promises and whether they promoted policies that were responsive to these groups’ demands. I wonder if similar accountability structures and feedback loops are needed to remind policymakers to listen to and hear what educators have to say. Ultimately, more efforts should be made to support educators’ meaningful and authentic engagement with policy.

Suggested Citation: Aydarova, E. (2024). Educators’ Policy Advocacy. Paper presented at the International Research Workshop on Teachers as Lifelong Learners. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning and Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China, June 12 – 14.